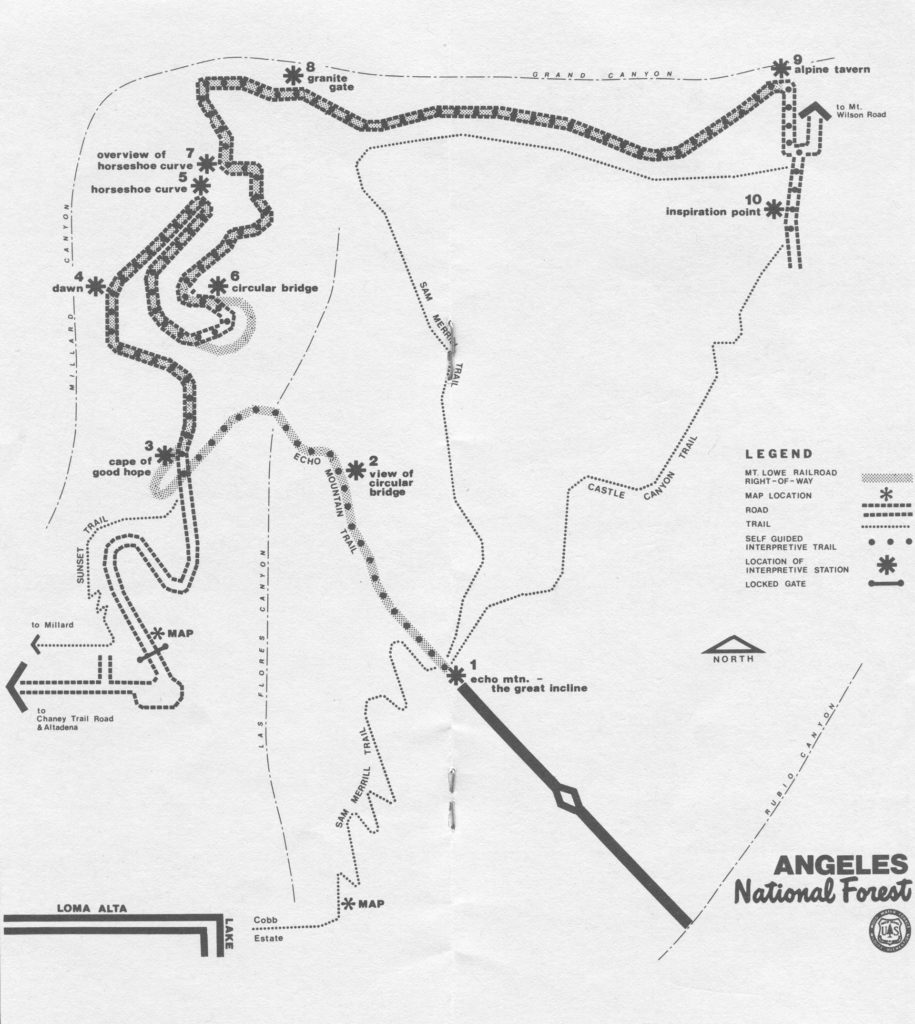

The Alpine Division was a narrow-gauge railway that extended for five miles from the summit of Echo Mountain to the Alpine Tavern at Crystal Springs. The gentle 7% grade incorporated a gain in elevation from 3,200 feet at Echo Mountain to 4,400 feet at Alpine Tavern. The gentler slope enabled the passengers to enjoy beautiful views of the San Gabriel Mountains. Here is how one woman described the trip in her journal: “At [Echo Mountain we] had to change for a trolley car to go up still higher; a peculiar sensation [as] we go five miles higher winding up the mountain, a horseshoe curve, a most wonderful ride. “Not everyone thought this ride was wonderful, however. One passenger described the ride as “five appalling miles of alternating happiness and horror, ecstasy and dread”. It is interesting to note that the safety record was nearly perfect.

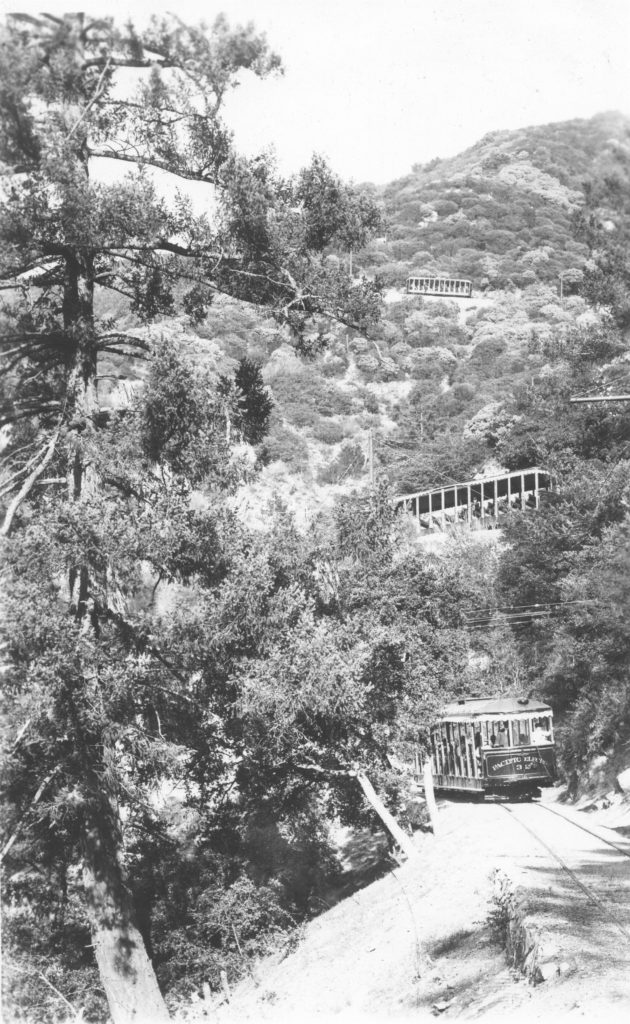

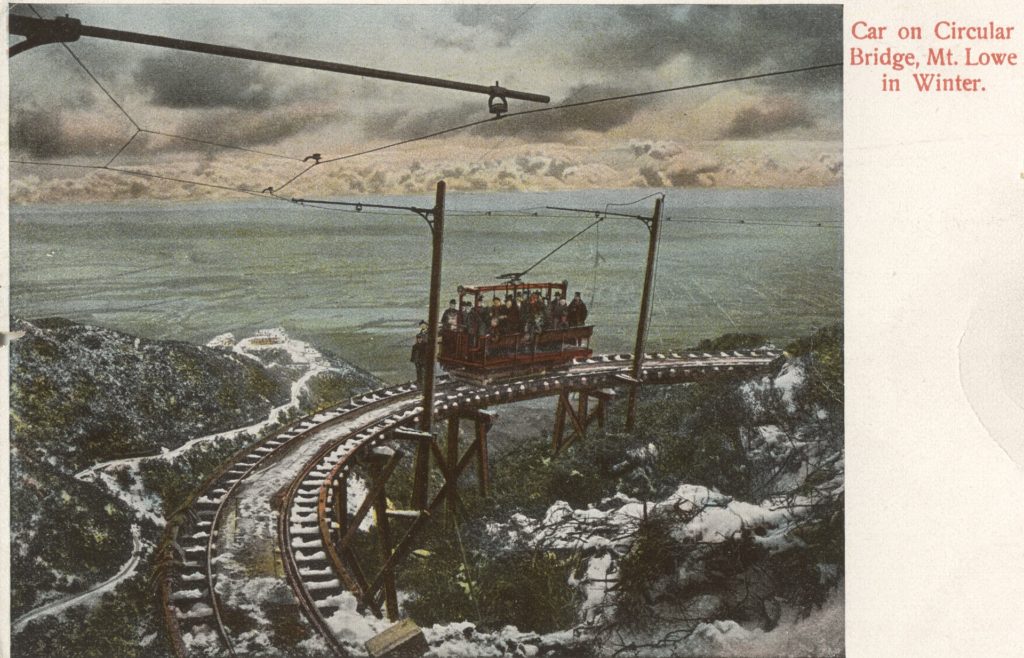

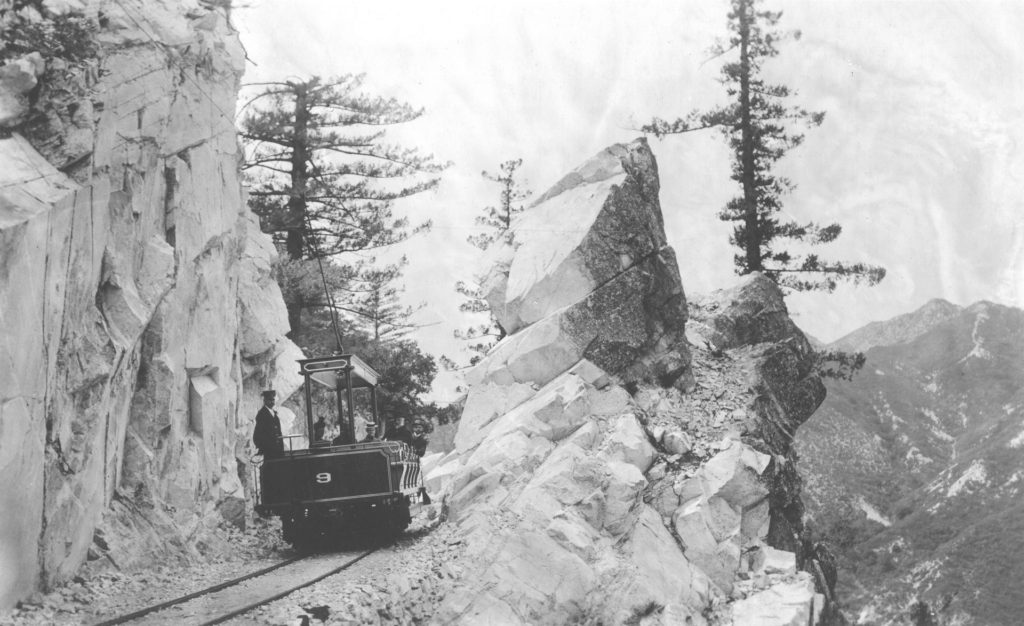

The trolley cars for the Alpine Division were rather quaint. The original cars were not equipped with roofs. The motorman stood at the front of the car with two large brake wheels and a controller. A few years after the opening of this section, roofs were added to protect the passengers from the weather. Passengers enjoyed watching the motorman manipulating the big brake wheel as the cars returned down the mountain.

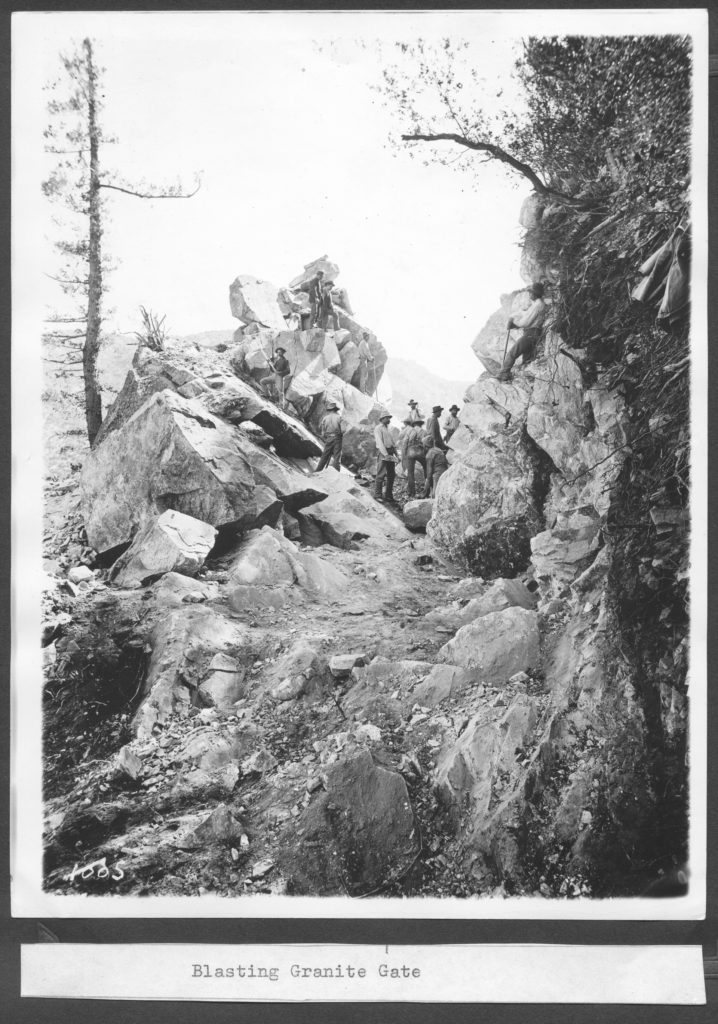

Construction

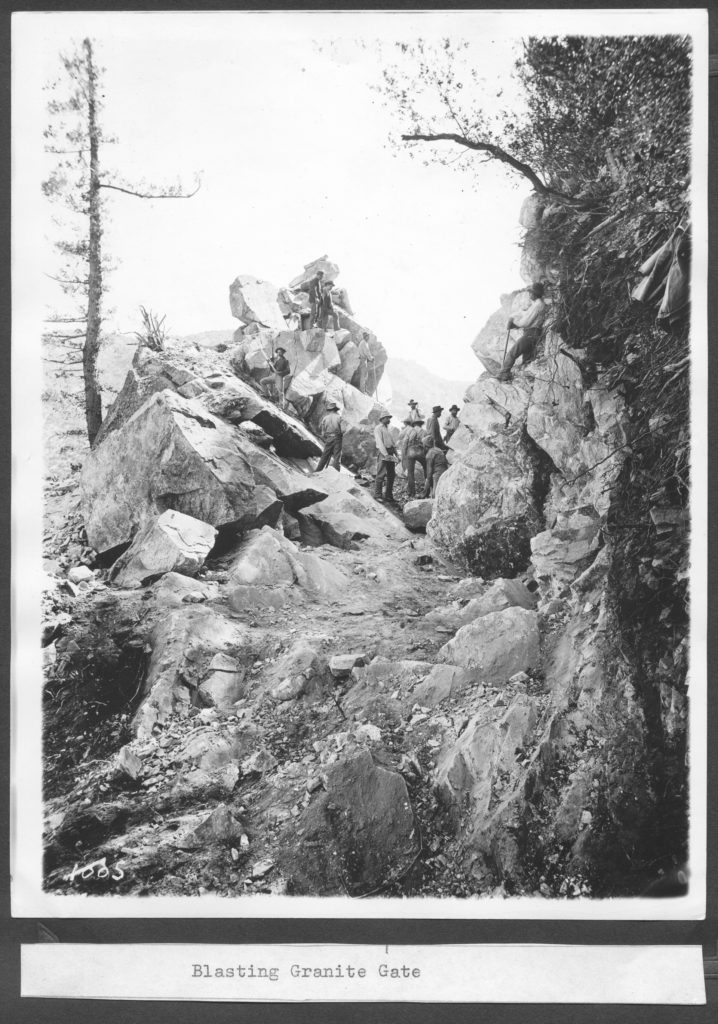

The construction of the Alpine Division began in November 1894, with the first service to Alpine Tavern in December, 1895. Many obstacles needed to be overcome during the building of this section of the railway. While a great deal of blasting and bridging needed to be done to complete the route, Professor Lowe told his engineers to “deface the natural beauty of the mountains only to insure safety” thus preserving the natural beauty of the mountains.

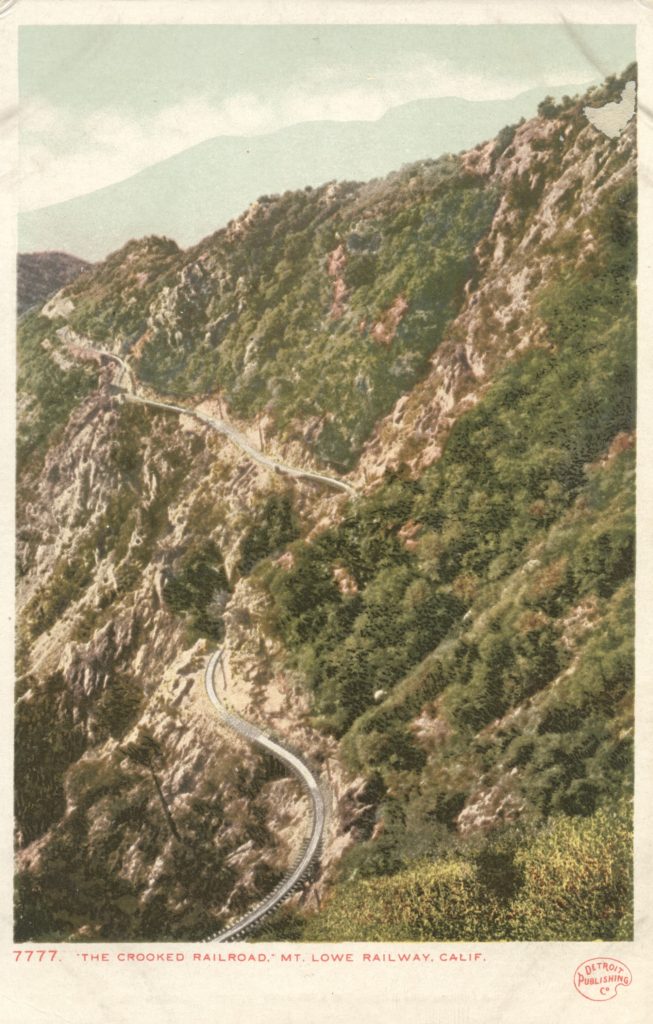

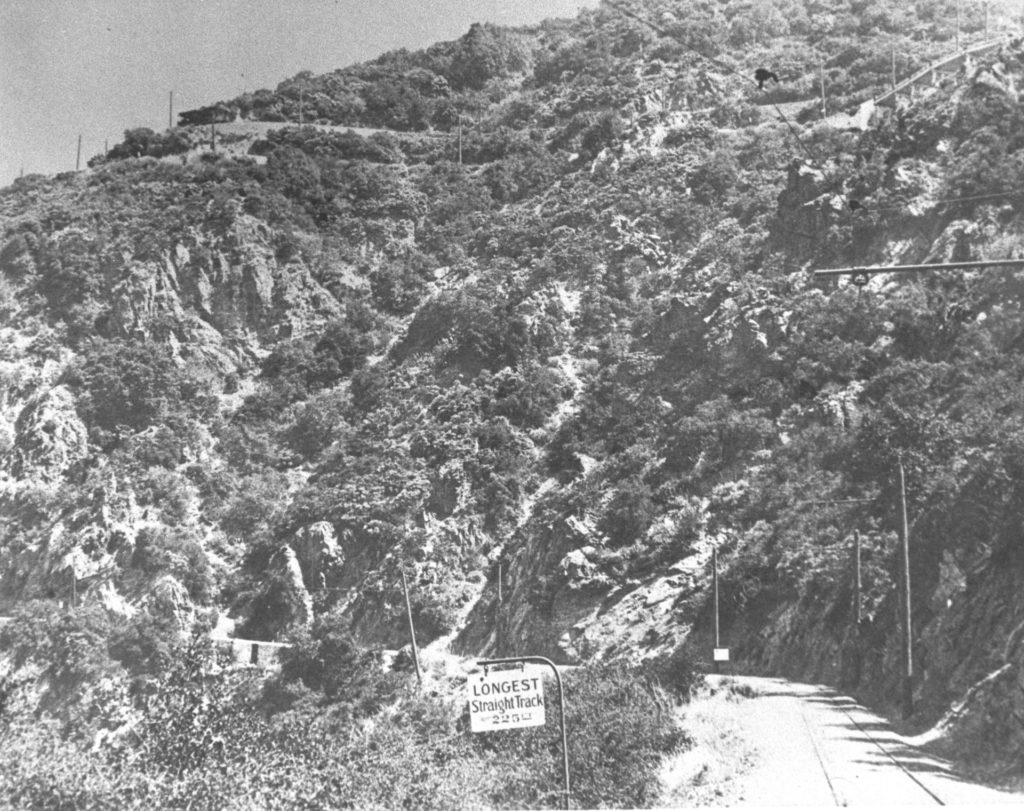

The rail bed followed the natural contour of the winding in and out of the little side canyons and took the rails over 100 trestles and 127 curves. The longest piece of straight track was only 225 feet. The climb of 1,500 feet carried the 30-pound rails on redwood ties that were laid on a shelf of solid granite. At one point along the line, nine different tracks could be seen rising above one another.

Visitors to Echo Mountain were very interested in the building of the new narrow gauge railroad to Alpine Tavern. To capitalize on their curiosity, Professor Lowe decided to make the emerging right-of-way available to tourists who, with rented horses or mules, could pay $2 to explore accessible portions of the future Alpine Division.

The Trip to Alpine Tavern

Mr. Winthrop Owen was a conductor on the Mount Lowe railway from 1927 to 1934. The following comments he made as his trolley passed by each section of the Alpine Division track were printed in the Pasadena Star-News in 1961.

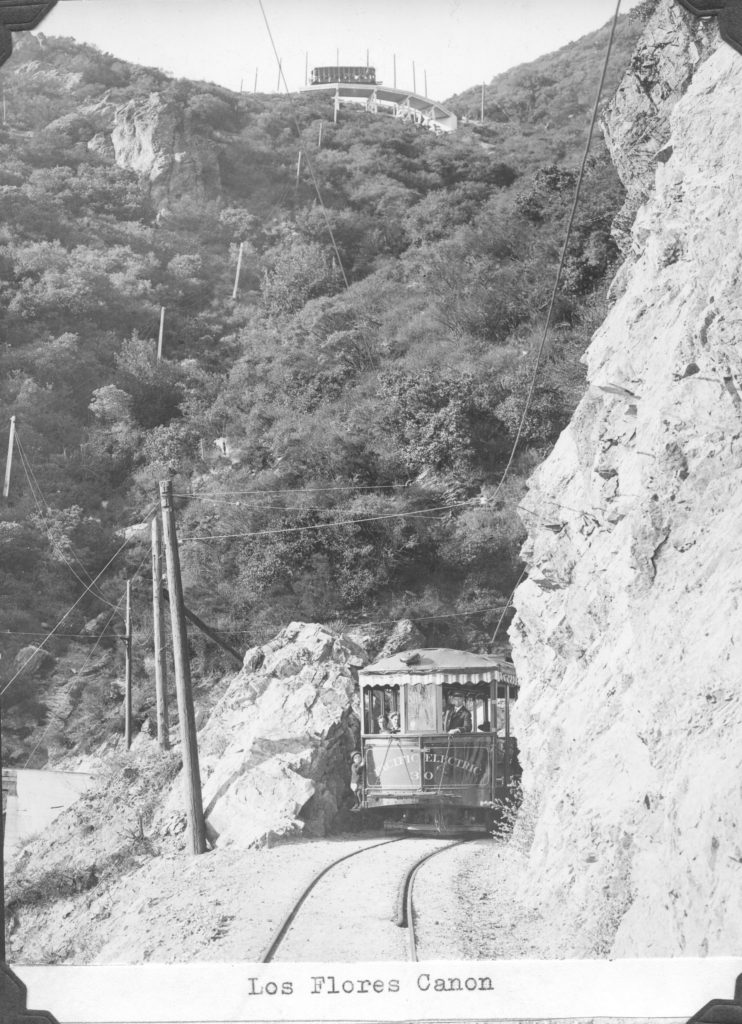

Las Flores Canyon and the Cape of Good Hope

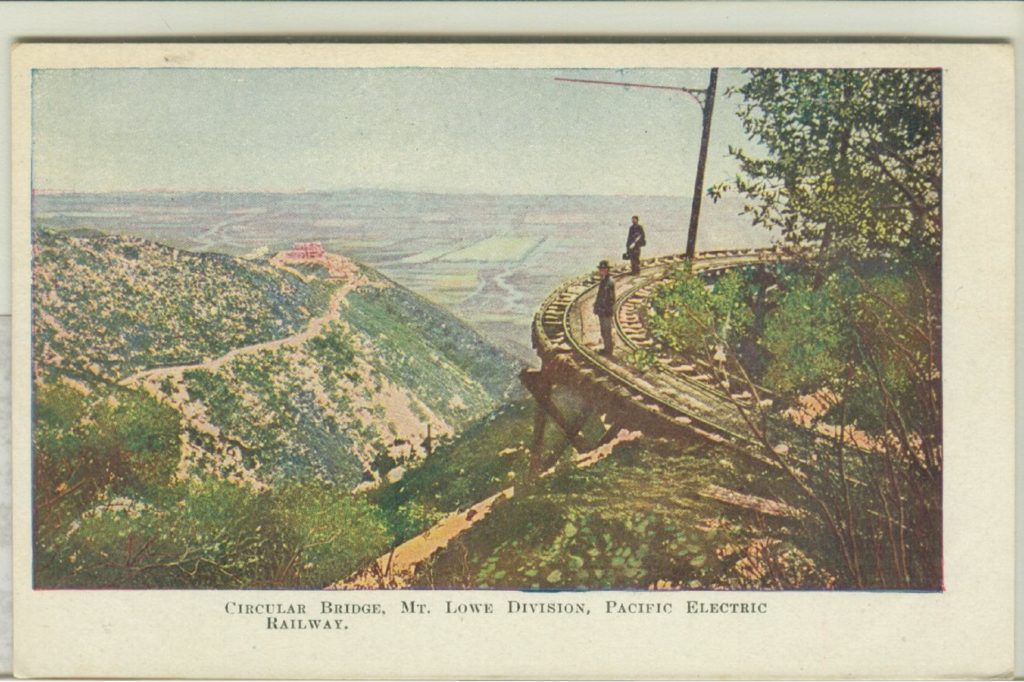

“You are now starting on the last three and one-half miles of this trolley trip. The canyon below you on the left is known as Las Flores Canyon, a Spanish term meaning The Canyon of Flowers. It derives its name from the thousands of native wildflowers which bloom in the canyon each spring. Looking across the canyon to the ridge above you, may be seen the world famous Circular Bridge which we will pass over in about 15 minutes.” (Winthrop Owen)

The first section of the Alpine Division proved to be one of the most challenging. Beginning at the top of the Great Incline in front of the Echo Mountain House, the roadbed ran west to the edge of Echo Mountain, then north, clinging to the walls of Las Flores Canyon. It included trestle-work on eleven bridges built in the first quarter mile of track. At the head of Las Flores Canyon was a sharp turn called the Cape of Good Hope, which led to the entrance of Millard Canyon.

Dawn Mine and Devil’s Slide

“Below us in the canyon at this point is Dawn Mine, an early gold-mining venture. Several of the tunnels still remain but are boarded up.” (Winthrop Owen)

The Dawn Mine was an abandoned gold mine whose shafts were later used to gather the water supply for Altadena and Pasadena. Hikers who wanted to have a break from the trolley’s steep assent from Echo Mountain to Crystal Springs used the Dawn Mine Station to explore the trails leading to the mine.

“We are now crossing the Devil’s Slide, so named because the loose, decomposed granite, of which it is composed, makes treacherous footing for the unwary hiker on the steep slope” (Winthrop Owen)

Near Dawn Mine was a geologic feature known as Devil’s Slide, which featured a large patch of decomposed granite.

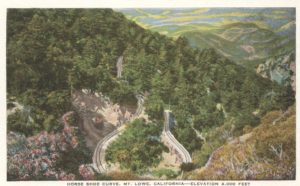

Horse Shoe Curve

“Now we approach Horse Shoe Curve. Because the steepness of the grade at this point causes a heavy strain on the gears and motors of the car, it will be appreciated if you will all lean forward on an effort to relieve that added strain.” (Winthrop Owen)

Horse Shoe Curve was one of the switchbacks that the electric railway had to make to be able to continue on a fairly level path up the mountain while climbing out of Millard Canyon. It was a 120º curve and led to one of the steepest grades on the Alpine Division at 7%. When the railway was first built the curve was made of wooden trestles. Later the wooden trestles were upgraded with concrete supports.

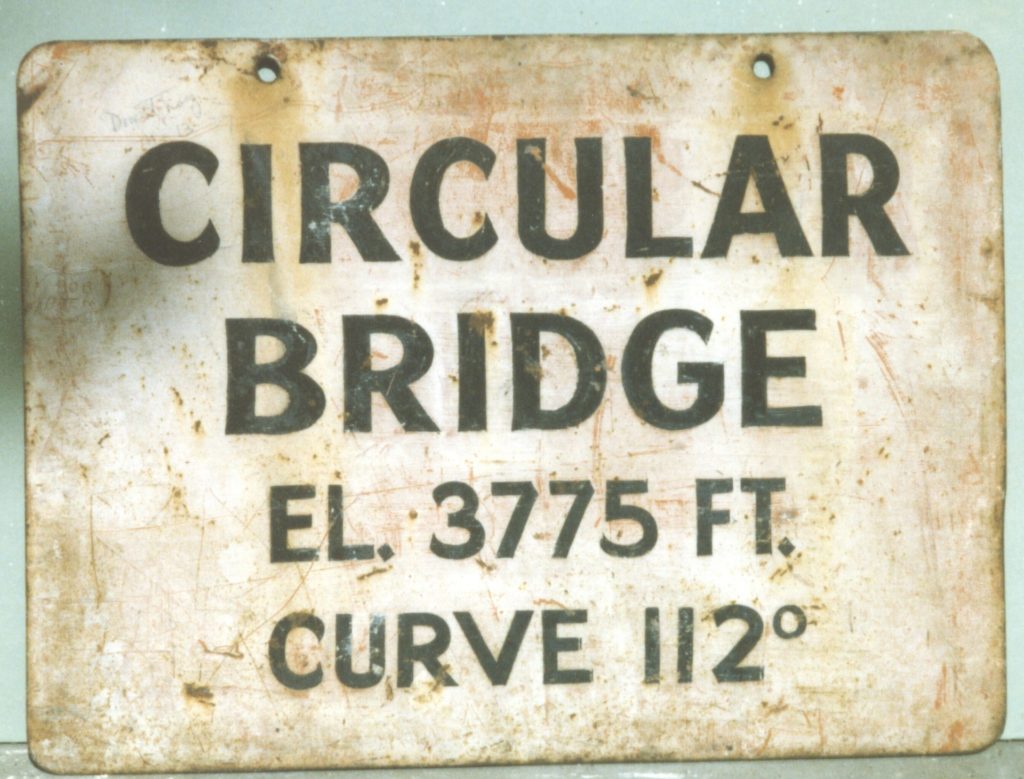

Circular Bridge

“We are now coming to the world-famous Circular Bridge. As we approach it, the precipice on the right is a sheer drop of almost 1000 feet. This bridge was the first bridge in the world designed for both the curve and an ascending grade. It is almost a complete circle nearly 400 feet in length with a better than 4% grade.” (Winthrop Owen)

Circular Bridge was considered a world-famous engineering landmark. The bridge was built on a 4.5% grade with a radius of 75 feet. The structure rested on solid rock and the upper end was 20 feet higher than the lower end. It was engineer Macpherson’s answer to the problem of getting the railway into the upper reaches of the steep canyon known as the Grand Canyon of the Millard. While riding the railway the passengers had the sensation of being suspended in mid air as they passed over the bridge. The bridge was visible early in the trip as the cars progressed towards the Cape of Good Hope. At a distance of only 1.75 mile by rail, it took 15 minutes to get there.

Sunset Point

“Looking below on the left may be seen Horseshoe Curve and the three elevations of track over which we have just passed. We are now approaching Sunset Point, from which beautiful sunsets over the mountain and the valley below may be viewed.” (Winthrop Owen)

From this location, riders could enjoy mountain views as well as valley views that stretched to the coastline of Long Beach, 30 miles away and Catalina beyond. And, of course, the sunset, if they were traveling at the right time of day.

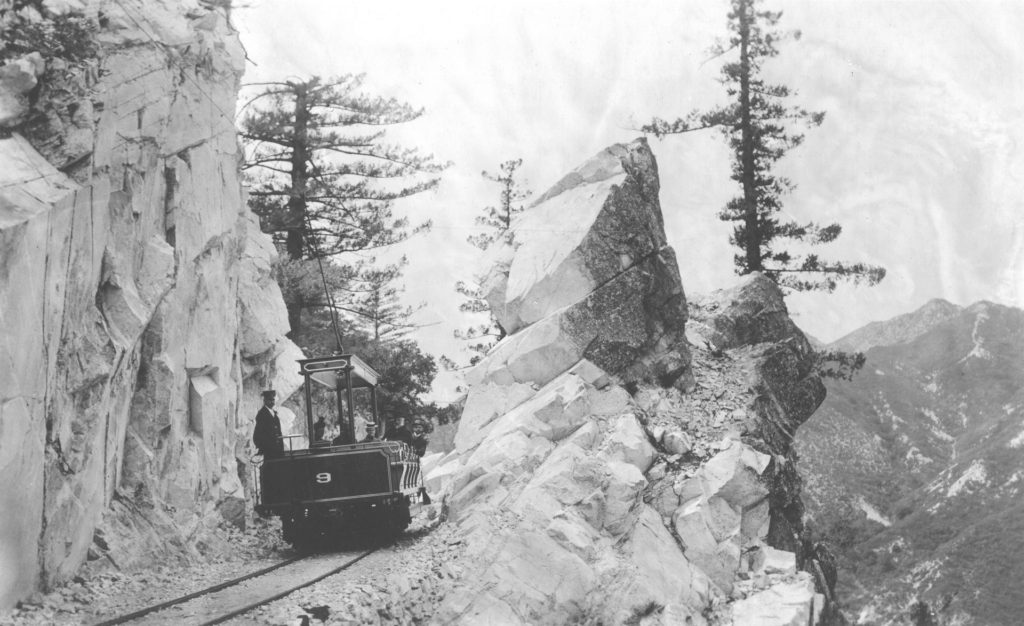

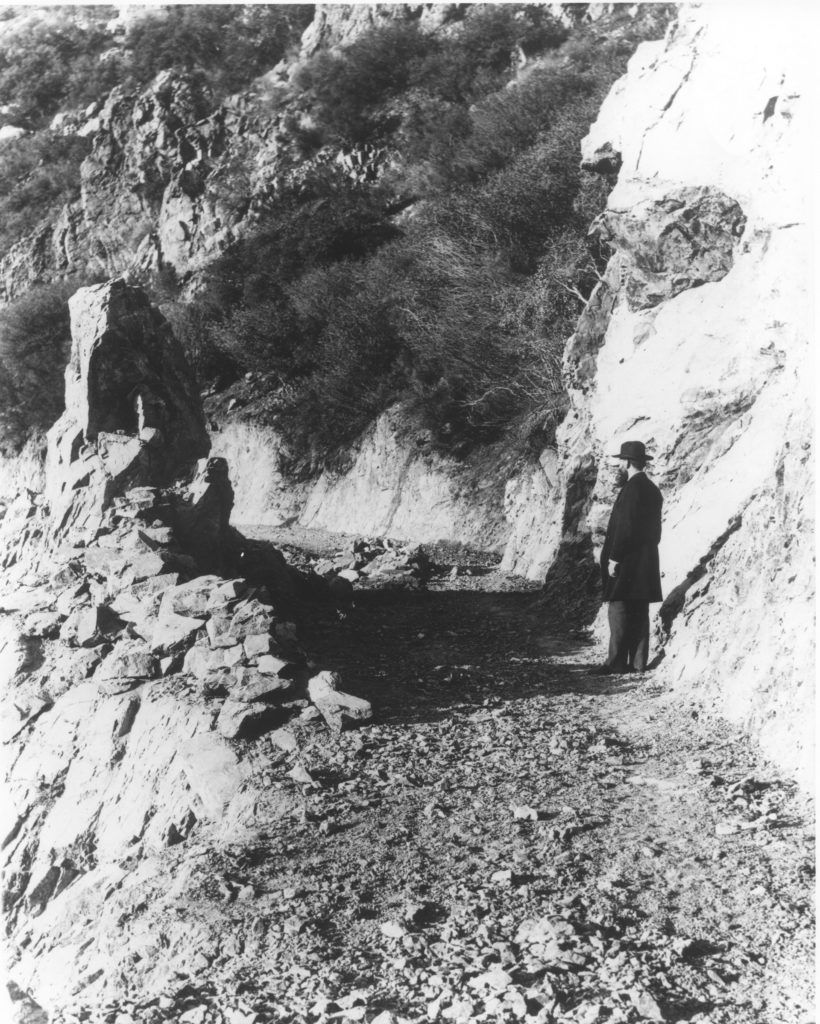

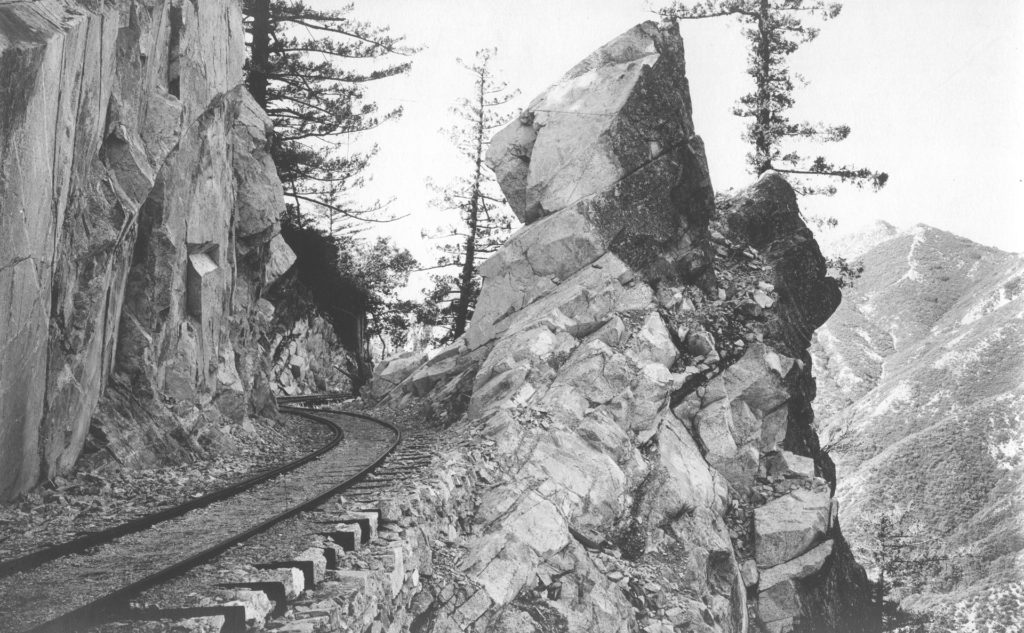

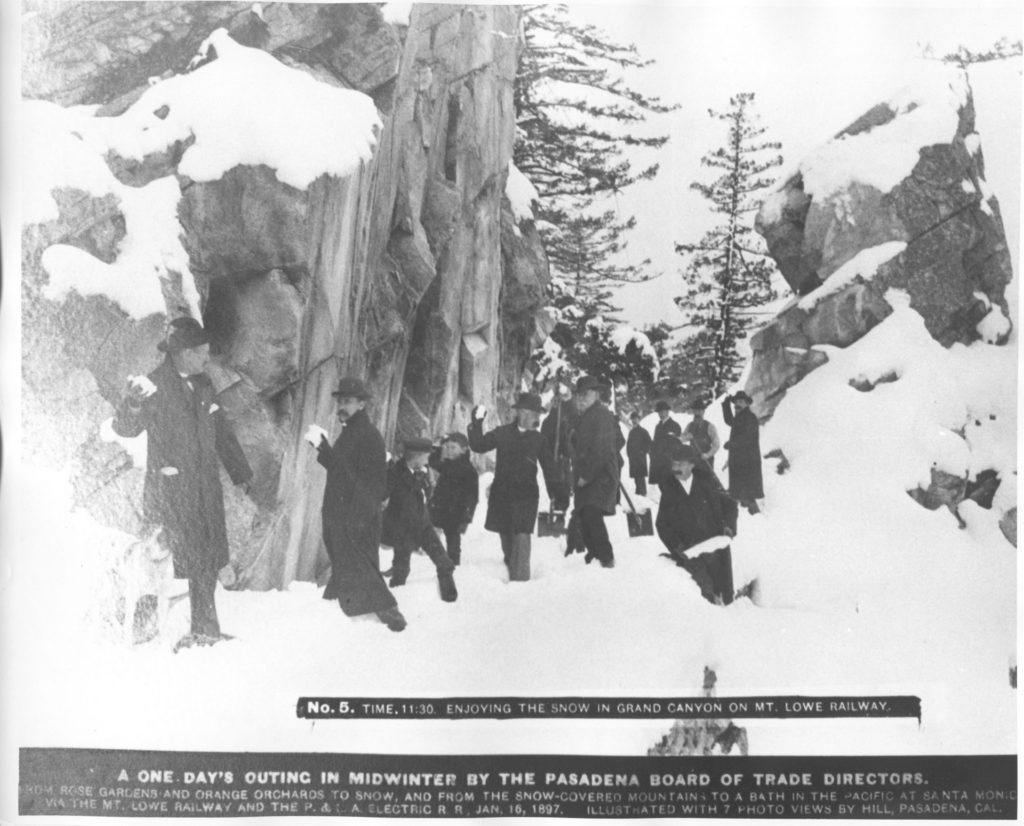

Granite Gate

“We are now coming to Granite Gate. You will observe that the roadbed has been blasted through solid granite. As we pass through the gate, a broad canyon below us comes into view. Called Grand Canyon, it is nearly a mile wide and more than 1,000 feet in depth.” (Winthrop Owen)

As the trolley approached Granite Gate, it ran through a dense grove of live oaks then westward to Sunset Point where beautiful sunsets could be observed. In order to build Granite Gate, thousands of cubic feet of granite rock were blasted away. Eight months were spent in the construction of this gateway. This section of the line was built entirely on a bed of rock carved from the mountainside.

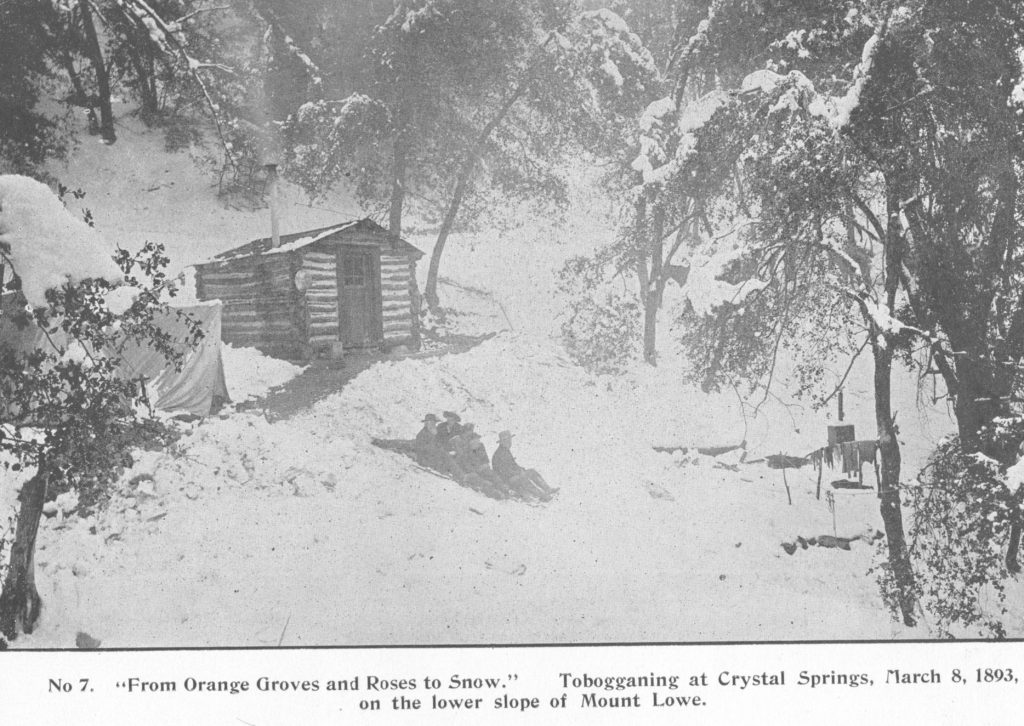

Crystal Springs and the End of the Line

“Mount Lowe (Alpine) Tavern is located at the head of this canyon [Grand Canyon] in a beautiful setting of Big Cone spruce [at Crystal Springs].” (Winthrop Owen)

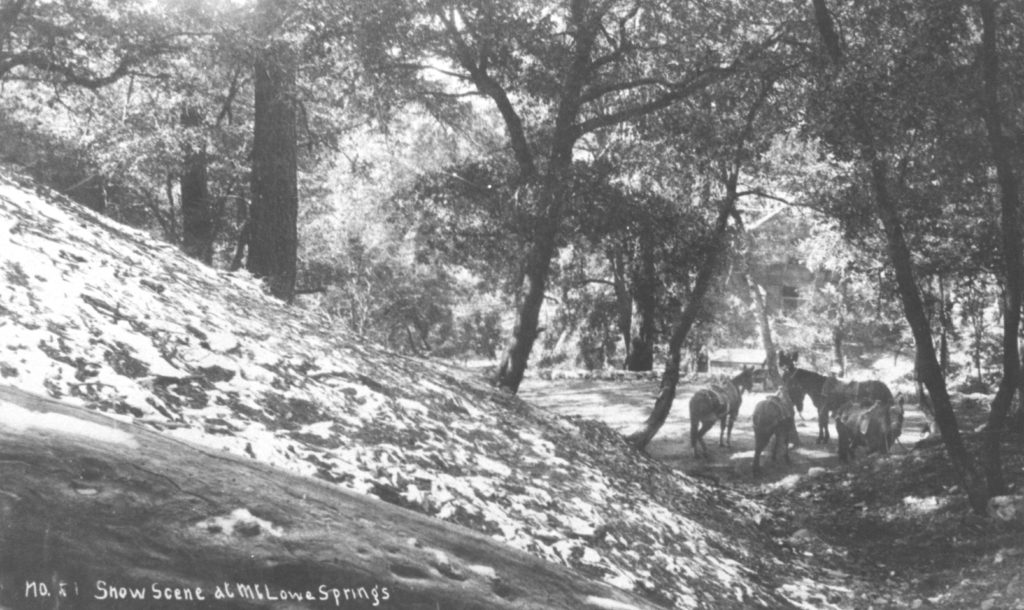

Professor Lowe selected a forested glen, at what was to become the terminus of the Alpine Division, as the location for Alpine Tavern. The area was described by Will L. Thrall in Trails Magazine ( Spring 1939), as “This delightful spot, known to many in the old days as Squirrel Springs, called by Lowe interests, Crystal Springs, and later, Mt. Lowe Spring, was a little narrow valley, beautifully forested and fed by a fine big spring of delicious water.” The site was a favorite picnic and for the Lowe family and later used as a construction camp for Alpine Division workers. At 4,400 feet, the location proved to be a perfect recreational resort – cool in the heat of summer and a snowy wonderland in the winter.