It took a lot of people to build, manage and maintain Mount Lowe, one of the greatest tourist attractions of its time. David Macpherson was, of course, the chief engineer, ably assisted by electrical engineer A.W. Decker and Andrew Hallidie with his plans for the incline cable. The Carson Brothers Construction Company built Echo Mountain House and the Macpherson trestle, and may have been responsible for building more of the railroad as well.

Fred T. Drew, manager of Rubio Canyon Junction, lived with his wife and four children in the Rubio Pavilion from 1905 to 1909. The family had moved to winter quarters in Pasadena, but all were on site when the disastrous storm struck the canyon. One of their sons was tragically lost, but the remainder of the family survived.

Guy Fess, Echo Mountain maintenance chief, spent 25 years as a mechanic on Echo Mountain, maintaining the cars and replacing cables every three years. After the Mount Lowe Railway closed, he and his wife stayed alone on Echo Mountain from 1936 to 1938. They were once marooned there for 17 days during heavy rains.

Mark. D. Sweringer, motorman on the railway, worked for Pacific Electric for 40 years. He wrote an article, “The Mount Lowe Line,” for the National Model Railroad Association Bulletin about his experiences. He rode the train from Los Angeles to Echo Mountain; then, while arriving passengers were having their souvenir photo taken, he would prepare the narrow gauge car that would take them the final three and a half miles to the tavern.

Sometimes on Saturday evening trips to Rubio Pavilion, he recalls, the motorman would be signaled by a cabbie. The train would then stop at the next grade crossing to pick up passengers who did not want to be seen boarding the Mount Lowe train in Los Angeles.

Al Lusher was in charge of the working crews for the Pacific Electric Railway, later renamed Pacific Electric. According to his niece, Enid Hollingsworth Park, “he worked first with Greeks, learning their language and working well with them until they gradually disappeared. The Chinese crew that came next – he liked them too and learned their ways and language. He enjoyed working with all of them, but his preference was for the Mexican crew he worked with for years. He enjoyed them so much that when he had his vacation he spent it in Mexico, getting to know them even better.”

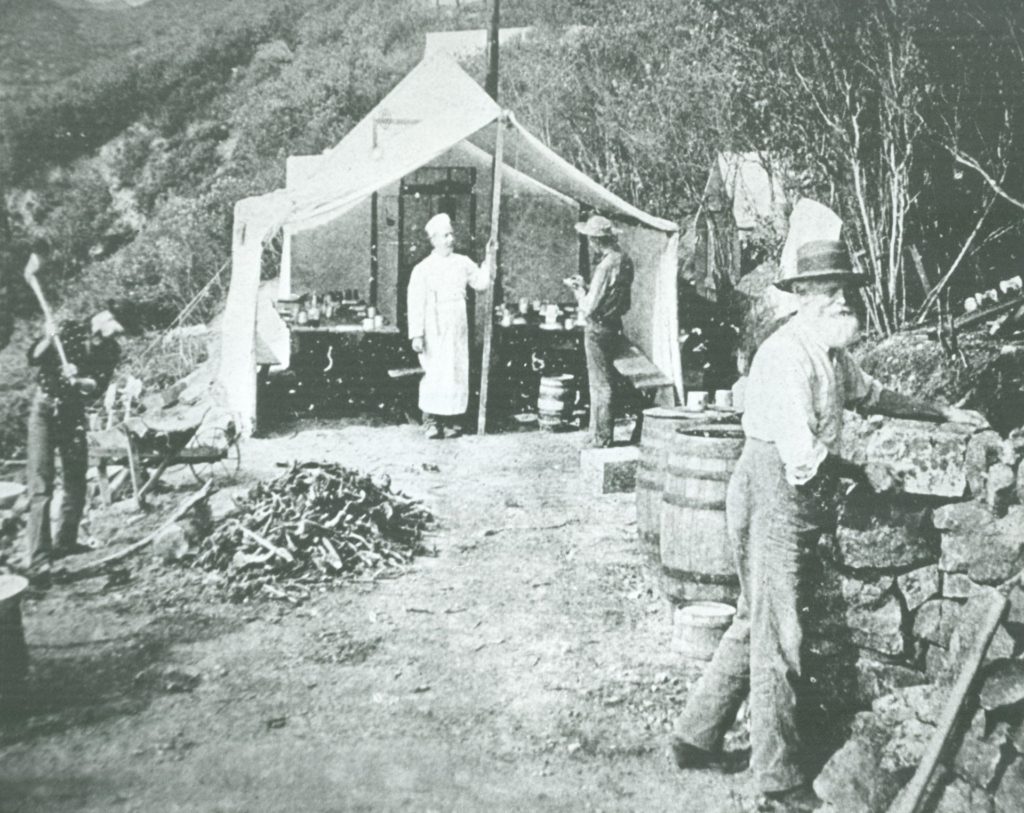

Mexican immigrant workers on Mount Lowe during the Pacific Electric era were the subject of Stacy Camp’s PhD dissertation, Materializing Inequality, the Archaeology of Citizenship and Race in Early 20th Century Los Angeles. Working with Stanford University, Southern California Electric and the National Forest Service, she combined information from a dig on Mount Echo with oral histories, documents and previously discovered artifacts to describe the lives of railroad workers and their families. Mexican workers were considered a vital labor resource in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, and Pacific Electric recruited them to repair and maintain the railroads. Men were encouraged to bring their families, as a way of ensuring their stability as a work force. Housed in section camps on the eastern and western sides of Echo Mountain, out of the sight of tourists, Mount Lowe’s Mexican workers were subject to the practice of Americanization, a program that tried to acquaint immigrants with their role in society “by teaching them English, trade-oriented work, gardening and housekeeping skills.”