Memorialized in “The Right Stuff,” the award-winning film about breaking the sound barrier and launching the space program, Florence “Pancho” Barnes’ life story is one of talent, strength of conviction and trailblazing against a tide of naysayers, much like her doting grandfather, Thaddeus Lowe. Florence Lowe was born Feb. 22nd, 1901 to Thaddeus Lowe Jr. in Pasadena, California. She was raised in a well-to-do family in a well-to-do city, before setting off on a life of adventure and accomplishment and heartbreak.

Grandfather Thaddeus Lowe saw a spark in his granddaughter (he called it “spunk”) that many saw in Lowe himself. She also inherited the genes of another of Pasadena’s most successful families. Florence Mae Dobbins, daughter of bicycling entrepreneur Horace Dobbins married Thad Lowe Jr. in 1895. As Leontine could trace her family back to french loyalist leaders, so could Florence trace hers directly to King Louis XVI. Their first child, Emmert, was born in 1896 and five years later, the family was blessed with a baby girl whose footsteps soon echoed in the halls of their 35-room mansion on the 1300 block of South Garfield in San Marino. It was built by Caroline Dobbins for her daughter’s new family – with bricks and stones from the family’s mansion in Philadelphia shipped to Pasadena for the task.

Even in early life, Pancho was described as “rough and tumble” and a bit of a “tomboy”. She was an avid and skilled young outdoorswoman who loved riding horses and getting into mischief. Her famous grandfather kept the bright-eyed and curious Pancho at his side whenever his business would allow and later Pancho would proudly recalled her grandfather as “the most shot-at man” of the Civil War. At the age of 10 she was introduced to the world of flight at the Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Airfield and was amazed at what she saw. No doubt this experience, as well as her grandfather’s history with balloons, influenced her later life choices.

When she was thirteen, her parents attempted to smooth out her rougher edges by enrolling her at Westridge School for Girls in Pasadena. After starting out with a solid B average in her first year at the strict and academic school, Pancho’s grades slipped at the end of her freshman year to C’s and D’s. She was then sent in 1916 to Ramona’s Convent, a boarding school in Alhambra where, within a month of her arrival, she became the school’s first runaway. Pancho saddled her horse and slipped out of the Convent’s stables late one night and rode off to a Tijuana racetrack. She slept in the stables at night and dressed as a man, rode horses, and caroused with gamblers, jockeys and the racetrack crowd by day. She was only 15 years old.

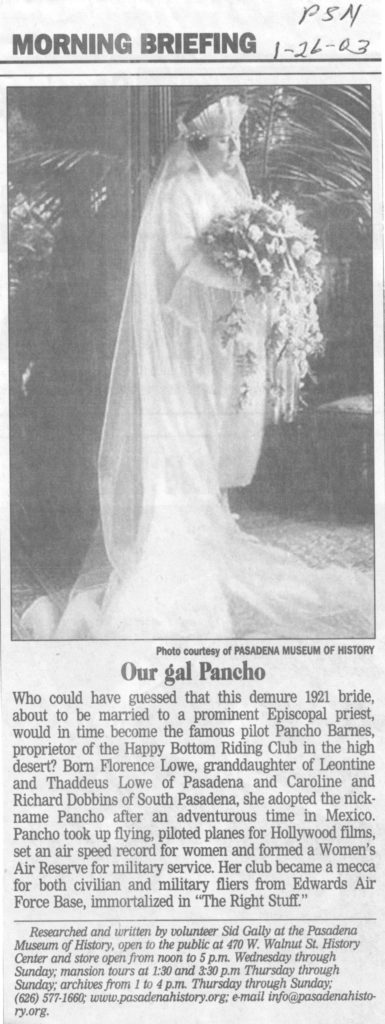

After a couple of weeks of rough comforts and wild times, she returned home to Pasadena in hopes that her parents would allow her to live at home. But instead she was sent to the very strict and proper Bishop’s School in La Jolla for the remainder of her high school education. In 1919, Pancho graduated and moved back to Pasadena where she was introduced to the man her parents had chosen as her future husband, a new pastor in South Pasadena named Calvin Rankin Barnes.

Pancho consented to the marriage to please her parents. Their engagement was announced in August of 1919, and the marriage took place 17 months later. In Oct. 1921 she gave birth to her only child, a boy named William Emmert. Even as Pancho tried to fill the shoes of motherhood, she looked for other activities to replace the excitement and daring of her unbridled youth. She enrolled her well-trained horses in the movies and became known around Hollywood for her riding and horse-training skills. She also joined the newly establish Flintridge Riding Club where General George Patton was a member and competed in the Los Angeles Ambassador horse shows. Dressed in identical clothing, she doubled for Aimee Semple Macpherson in the riding ring, as Aimee was not a good-enough rider to go round the ring at top speed.

The marriage was troubled from the start. Pancho was not cut out for a life as a minister’s wife, and Calvin found himself married to an earthy woman with non-Victorian ideas of her place in the world. The strains that were showing when her mother passed away in 1924 became greater. After inheriting over $500,000, Pancho asserted her newfound financial independence by skipping town and going on a cross-country train tour. Upon returning, she told her husband that she was going to come and go as she pleased and he could continue on his path to becoming a Bishop in the Episcopal Church without her help. She became very involved in the movie industry at this time and learned hands-on most of the jobs required on a film set. She also became known as a stunt rider and appeared in several films.

In 1927, again asserting her independence, she went on a cruise to South America. While on board, she struck up a passionate romance with a handsome fellow from Texas and though he accompanied her back to Pasadena and they briefly corresponded, they never saw each other again. Later in 1927, after a night of partying with her filmmaking friends, she jumped on board a ship with a half-dozen fellow adventurers for another cruise to South America. Their ship was blockaded in a Mexican harbor and bandits prevented its passengers from leaving. After a friend bribed a sympathetic townsman with whiskey, the two made their escape on burros and traveled through the Yucatan jungle, enjoying the sights and experiences Mexico had to offer. After she joked with her friend, Roger, about the small stature of his burro, calling him Don Quixote, he quipped back that her burro was even shorter so she must be Sancho Panza. She decided “Pancho” was a better name than “Sancho” (Pancho is Spanish for Frank – and she was certainly that) and from then on, Florence became Pancho. Upon her return to California, Pancho and Calvin’s relationship worsened and in July of 1928, the two formally separated.

Pancho decided it was time for her to become a pilot, something very rare for women in those days. Being an accomplished equestrian, movie industry employee and outdoorswoman, this was just the latest mountain she chose to climb. She began her lessons in the first few days of July and by July 6th , she bought her first plane, a Travel Air 9000. She is seen in a famous photo jumping her horse over the tail of this plane with a caption reading “I’m up in the air over my Travel Air!” On Sept. 6, 1928, she soloed for the first time and became her instructor, Ben Catlin’s, first female graduate. This was the beginning of a flying career few women could match in talent (and mischief). Within her first six months of flying solo, she barnstormed the church wherein her estranged husband was trying to give a sermon, flying three times around the steeple. She would laugh heartily as she told and retold this story throughout her life.

By 1929, Pancho and her stunt pilot friends were landing at her beach home in Laguna on a dirt runway she had built on the property. The constant stunt flying and dust kicked up by the planes landing and taking off led to community complaints to the city council. Some of the pilots’ activities were curbed, but the runway was used until 1931. Pancho also formed her own “Mystery Air Circus” which thrilled Sunday crowds with biplane stunts and parachutists. She helped support her flying through paying jobs – flying planes back and forth to Wichita, as Union Oil’s public relations representative, for example.

When word of a women’s cross country air race came through the grapevine, Pancho was all ears. The air industry was in its infancy and needed publicity to change the common perception that flying was complex and dangerous. Women flying in safe planes in a race over long distances worked well for the airplane manufacturers, airports and oil companies and Pancho used the air races to write her name in the sky. The best 100 or so women pilots in the country, including both Pancho and Amelia Earhart, soon formed a club called the Flying 99’s and competed for the title of fastest woman on earth. On August 4th, 1930, Pancho Barnes flew her Beech Mystery Ship over a 3-kilometer course at an average speed of almost 197 miles per hour. She had beaten Amelia’s record and now stood on top of the pyramid. She was the fastest woman on earth.

If 1930 was Pancho’s zenith in powered air flight, 1935 was the end of her life as part of the San Marino elite. Years of enjoying a rough and tumble pilot’s life plus the Great Depression had whittled Pancho’s fortune down to nothing. She leased her San Marino mansion and moved to a horse ranch near an airstrip in the Mojave Desert. There she was invited to join a social group called the “Ladies of Muroc”, but her crude language and gruff manner made the ladies change their minds and she was not asked to return. Pancho bought cows and goats and delivered milk at 40 cents a quart to Borax and the small Army Air Corps and the National Guard division which both used nearby dry Rogers Lake for artillery and bombing practice. The milk deliveries grew to include the town of Mojave and the expanding Air Force corps, which grew in the late 30’s as civilian pilots were trained to combat the growing threat posed by Adolf Hitler.

There was a waiting list to get into the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which became effective in October of 1939. Pancho had a hangar built on her 80-acre property so she could qualify as a secondary school to help train the overflow while they waited to begin formal training. She ran ads in the local papers and soon Pancho’s Fly Inn Ranch was born. By 1942, Muroc was defined as an airbase and Pancho’s ranch became well known to the pilots and their superiors, including officers and pilots from Jimmy Doolittle on down the line. Pancho would invite the pilots over for tasty dinners which contrasted favorably with their meager rations and the evenings often ended with pilots spending the night on the couches or floors of Pancho’s house. She built a nice corral, offered riding lessons and horses for rent, added rooms for tired pilots to stay the night at Pancho’s Fly Inn bar and motel, and hired some attractive hostesses.

Pancho was in her element at the Fly Inn Ranch. She had top brass and plenty of pilots to carouse with and entertain. At some point during the war, the name changed to the Happy Bottom Riding Club. Pancho was serving whiskey to and drinking with the likes of General Dwight Eisenhower and test pilots Chuck Yeager and Slick Goodlin, and hosting Wednesday night dances with as many as 400 people in attendance. The club was gaining a reputation as the place where all the pilots went after flying to loosen up and have a good time. But eventually the top brass changes at every air base, and Muroc was no different. The new regime put Pancho’s Happy Bottom Riding Club off limits to Air Force personnel.

In 1952, Pancho was taken to court by the U.S. Air Force as they tried to force her to sell her ranch of 17 years to the government to make way for a new runway. She won a couple of tough battles in court, but sadly, the ranch burned down in 1953. While Pancho’s beloved horses and most of the hotel rooms were saved, her possessions were all lost. She continued her vigorous court battle, arguing that her grandfather should be considered the first member of the U.S. Air Force for his reconnaissance work done during the Civil War. She eventually won a settlement for nearly $500,000, but was forced to leave the ranch to the bulldozers and the runway building crew.

Pancho moved about 30 miles north to a ranch in the Antelope valley with plans to build a working dude ranch similar to the Happy Bottom Riding Club she would call Gypsy Springs. Her dream of the Gypsy Springs resort was never quite realized as her health was failing and her finances precarious. Pancho spent her last years in her desert home with her horses, dogs and a small group of friends before passing away in 1975.

Well loved and respected by the greatest of aviators and their commanders, she received many honors in her final years, including a 70th birthday celebration attended by many well-known aviators like Jimmy Doolittle and Buzz Aldrin. She had the same sort of stuff coursing through her veins as her brilliant grandfather had before her – “The Right Stuff,” some would say.