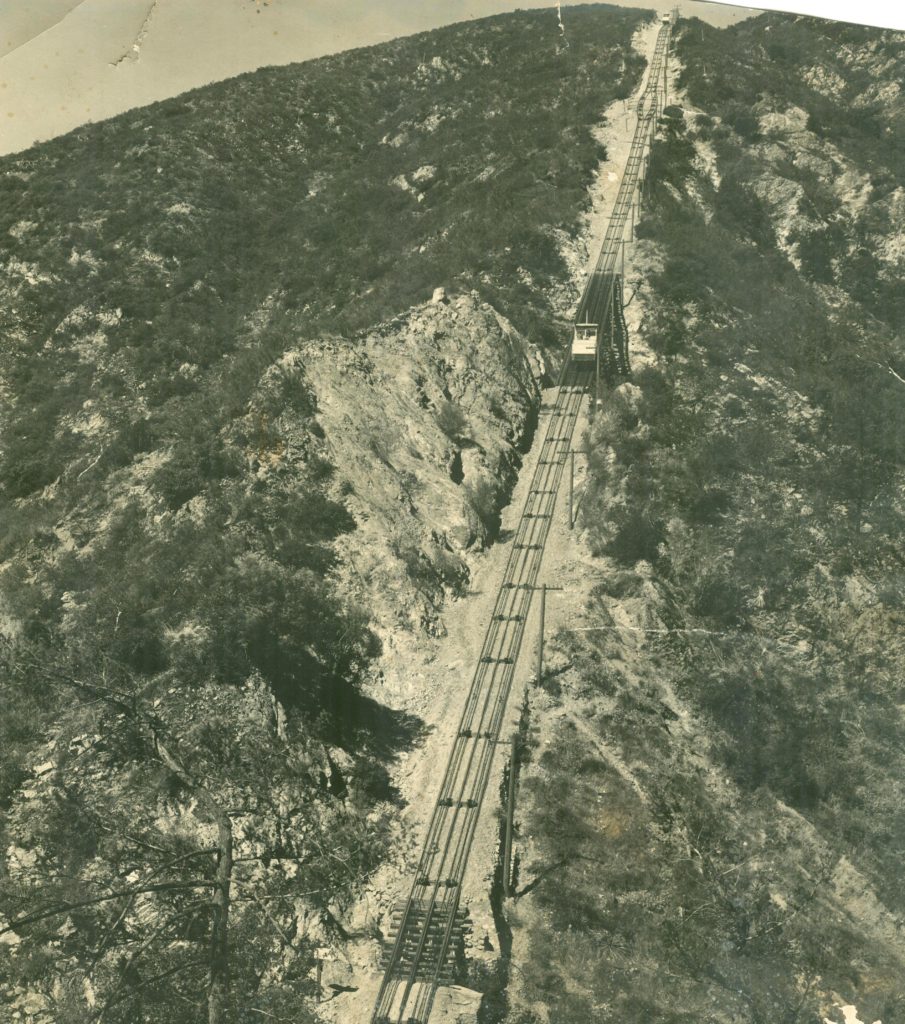

The Incline is a steep (60% grade) section of the Mt. Lowe rail system designed to carry passengers up a cable funicular railway to a mountaintop hotel, 1,500 feet above the Rubio Canyon floor. Work on the Incline section began in April 1892 and was finished in time for opening day on July 4, 1893.

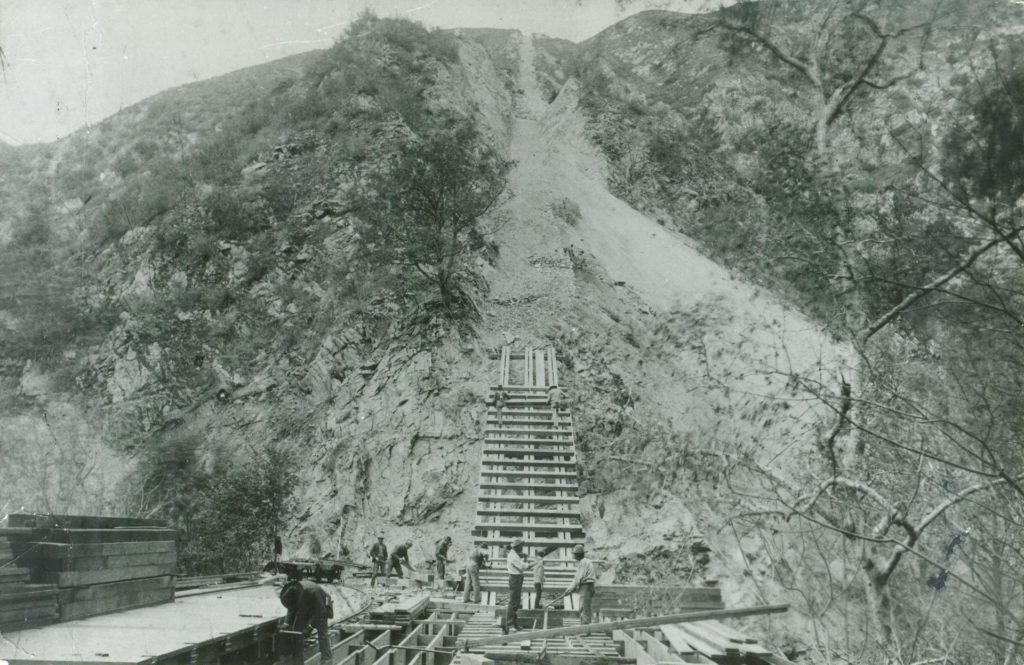

Construction

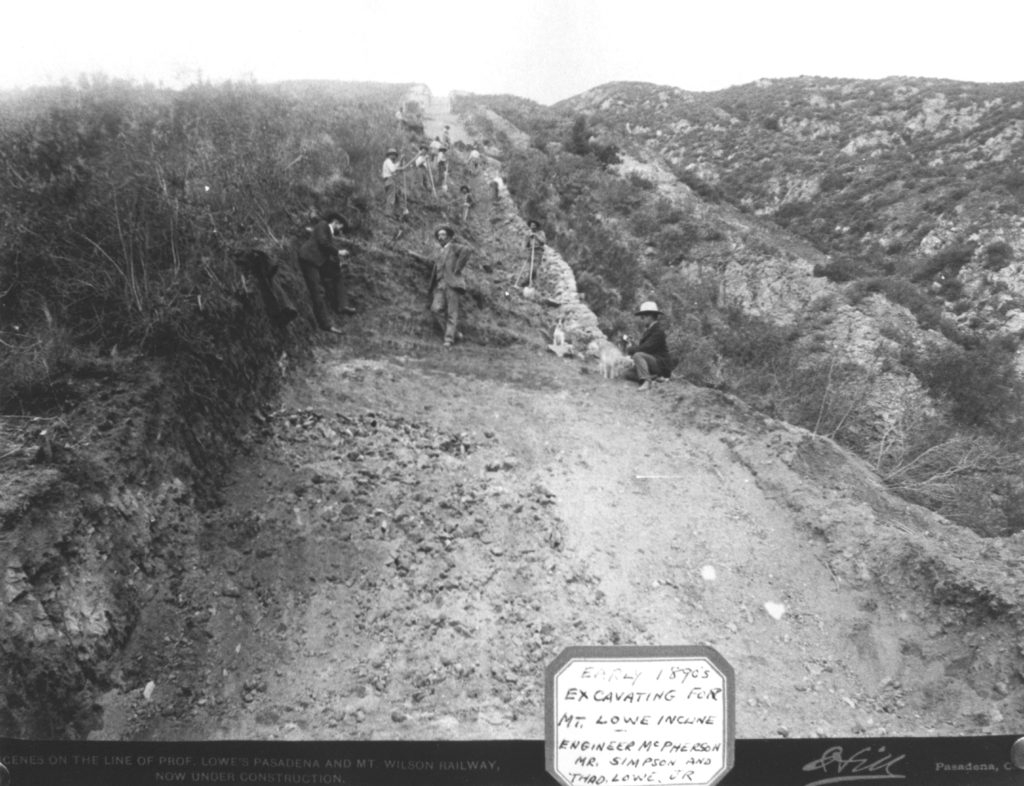

Construction teams were gathered by Macpherson at a time when laborers in California were well experienced with railroad construction and mining. These skill sets were in demand on the Incline as no machinery to assist in construction was practical at the secluded and rugged incline site. The first step was grading the hillside to a consistent level for the laying of two sets of track – one for cars going up and the other with cars coming down. Laborers graded the ascent by hand, and burros were initially used to haul materials. Next was the bridging of two deep ravines in the hillside. Once track was laid, cable was needed to string up the hillside, and a method of powering the cable grip wheel and a power source for the system needed to be built.

Grading was performed under the supervision of Macpherson, an experienced railway designer and builder. The daunting 60-degree grade and the thick granite layers of the rugged San Gabriel Mountains proved more than challenging. In some places burros refused to budge and men had to move rocks and soil with buckets. Teams of laborers using shovels and railroad ties hitched to heavy ropes were the most effective way to prepare the upslope for tracks. It took 8 grueling months to cut through the granite and build the required bridging.

The Macpherson Trestle

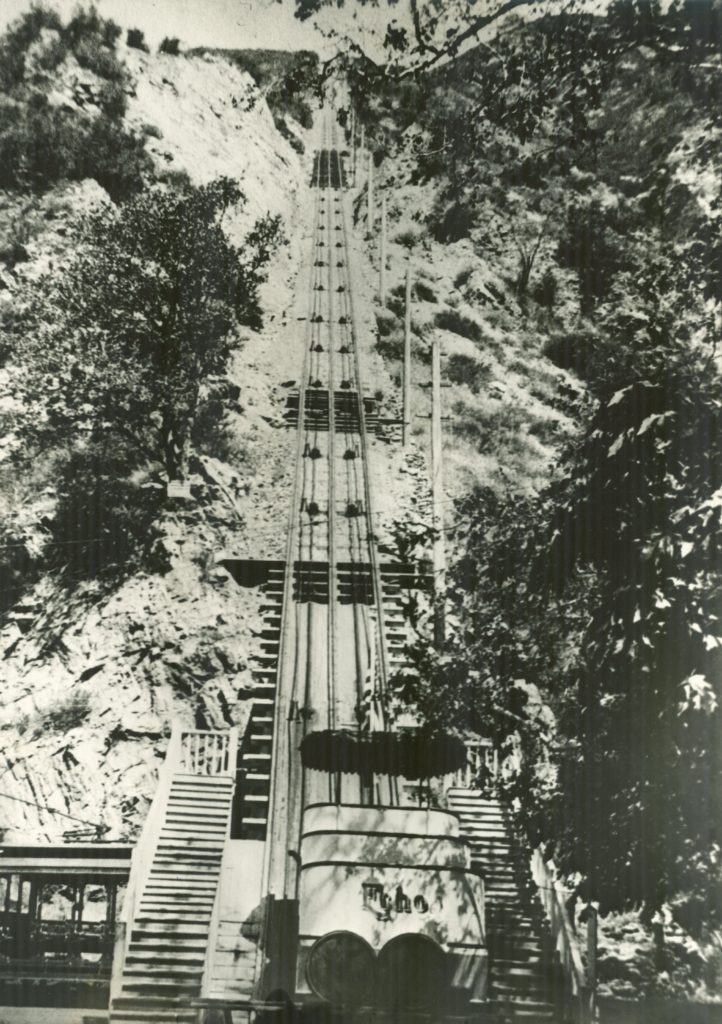

The Macpherson Trestle, an extraordinary engineering achievement for 1893 or any other time, was built to bridge an enormous chasm in the mountainside, about a third of the way up the incline. The ravine was over 200 feet long and deep, big enough to fit a four story building inside. The top end was 114 feet higher than the bottom. In its day, the trestle was a marvel of rail engineering, and Macpherson was firmly at the reins from conception to construction to successful operation. The Macpherson Trestle burned in 1935, was rebuilt and reopened in 1936, and dismantled in the 1940s.

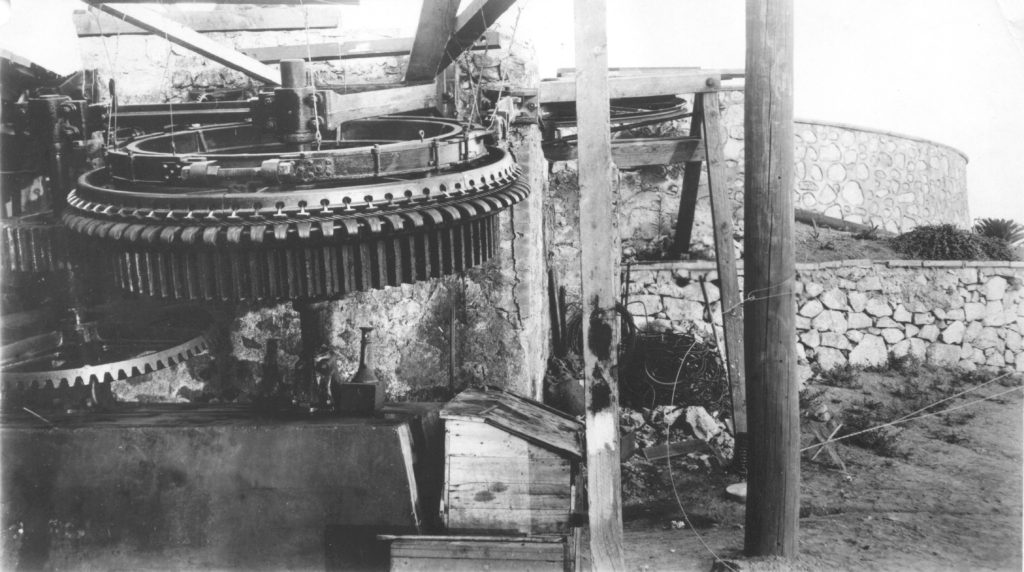

Incline Electricity and Cables

In October 1892, a large “wire rope” cable was run part-way up the Incline to assist in moving construction materials up the slope. Materials were transferred to burros for the remainder of the climb, until December 1892 when the cable was hauled all the way to the top of the Incline via a wooden horse-drawn windlass. The cable weighed over three thousand pounds in its entirety.

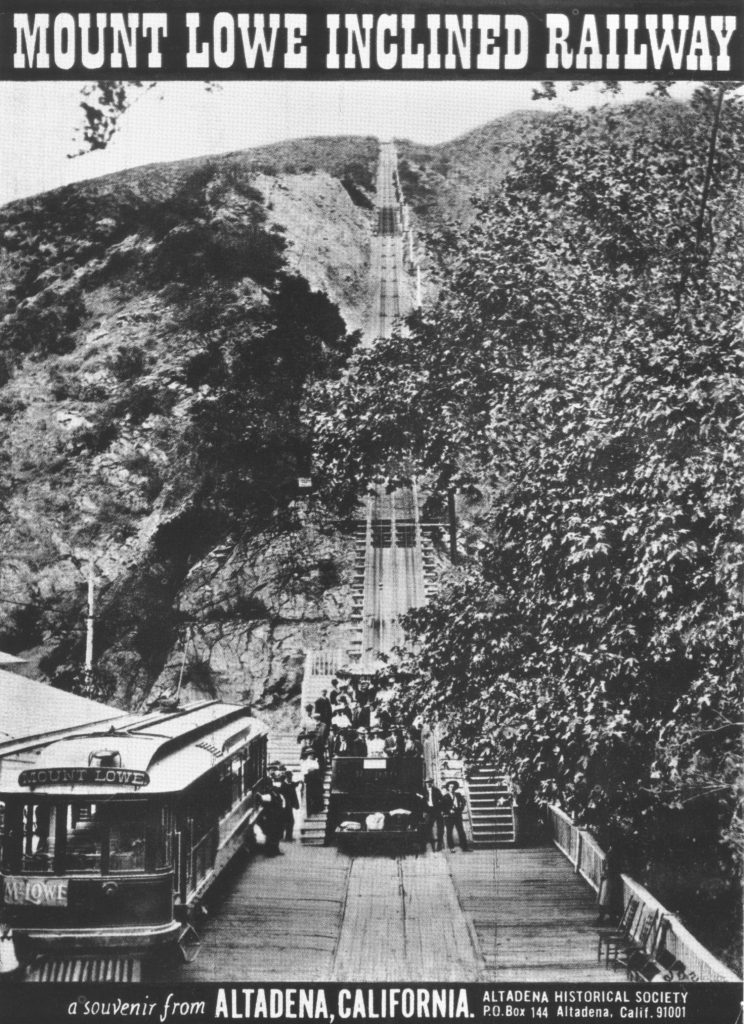

Chariots and Their Riders

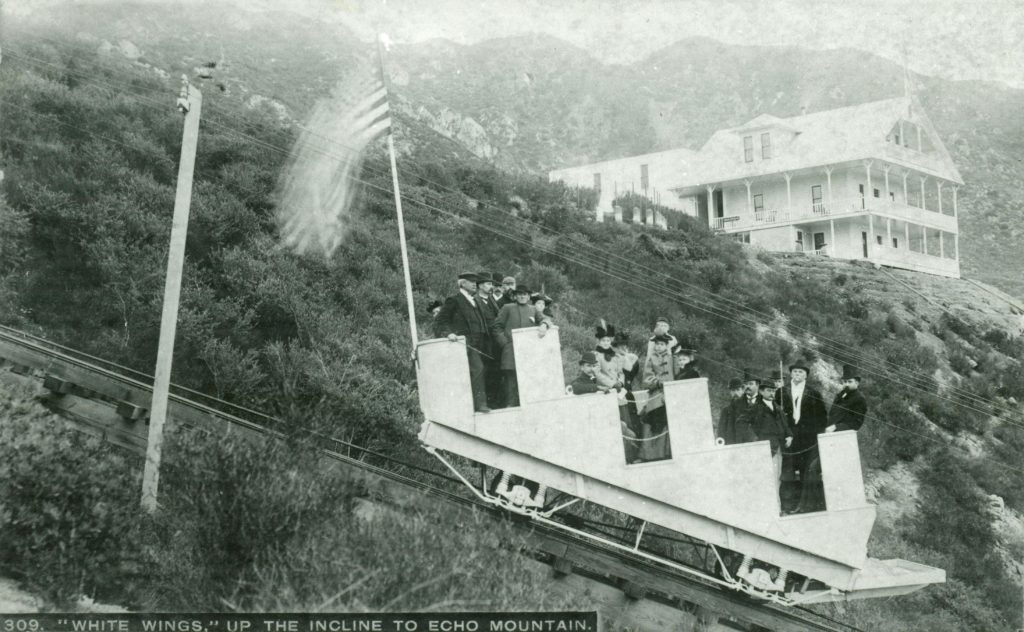

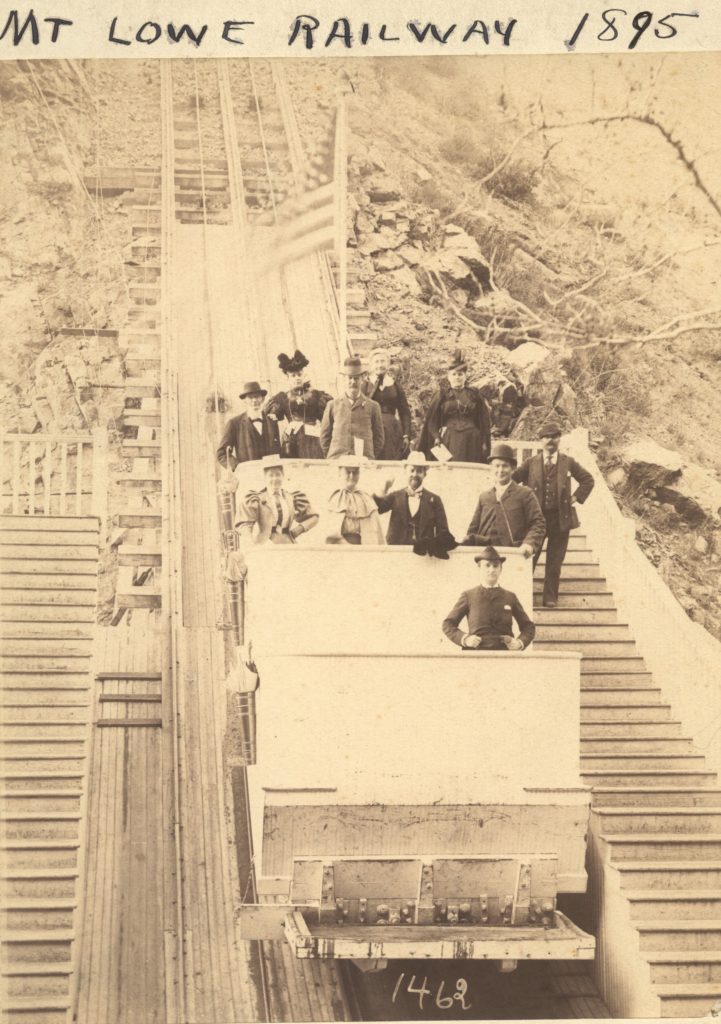

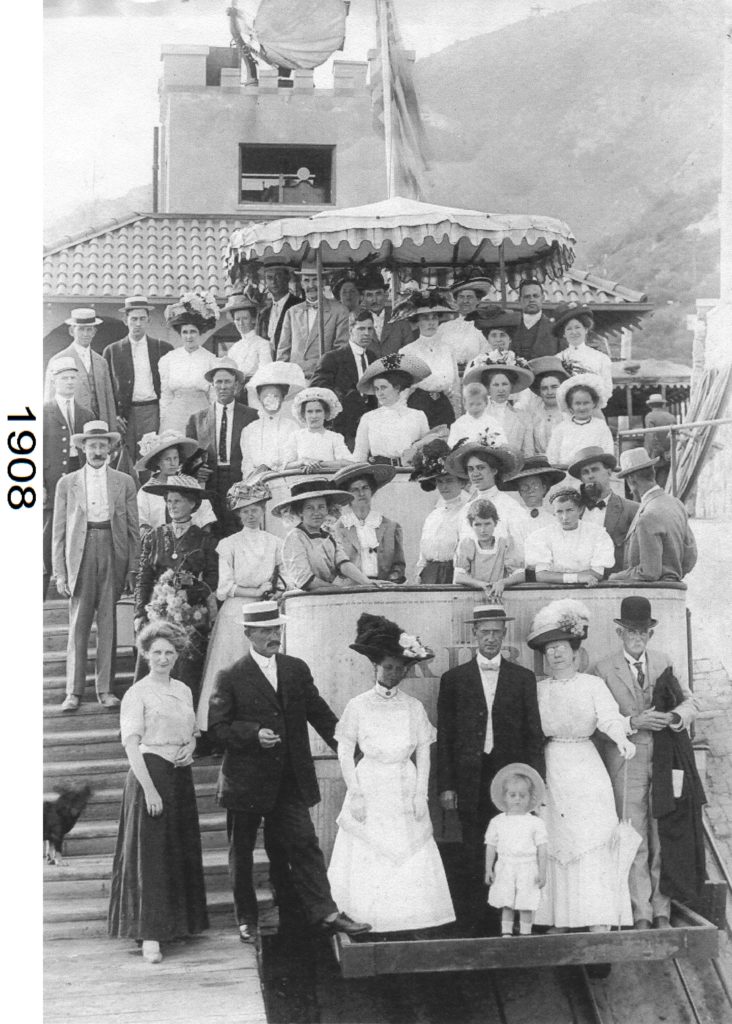

The vehicles used to take passengers comfortably on their 6 minute ascent to Echo Mountain were called opera box cars or white chariots by their early riders. Professor Lowe had designed the 7-foot by 18-foot cars, each built to comfortably carry 30 to 60 people. Early chariots were used to haul construction materials to the Echo Mountain hotel construction site, eventually replacing burros as the primary means of delivering materials. Leaders of industry, governors and other notables all rode the chariots to Echo Mountain during its heyday, and the ride up the Incline was heralded as the greatest spectacle in all of California. The Incline cars took over 160,000 patrons to Echo Mountain in 1921, their busiest year. It is a testament to its designers, builders and maintainers, that the Incline never suffered a fatal accident in over 40 years of continuous service!

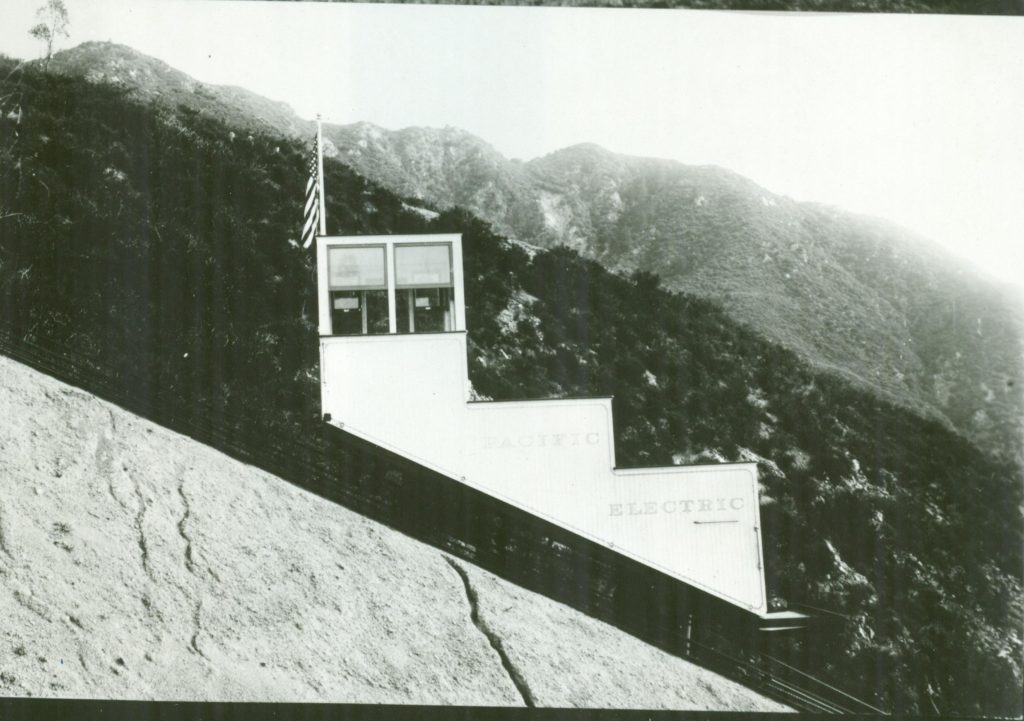

Souvenir photos taken by Charles Lawrence when the Incline cars reached Echo Mountain tell us much about Incline cars and riders during the railway’s years of operation. From its opening in 1894 to its final days in 1936, these cars went through a few evolutions which allow for accurate dating of the photographs. From 1892 to 1902, the chariots were open cars, painted white with little protection from the elements. In 1902, when the Pacific Electric under Henry Huntington takes over, the cars were named Echo and Rubio, with bold script painted on their still white car fronts. The passengers also got some weather protection in the form of an awning which protected the top of the three leveled car from sun and rain.

The next change occurred in 1905 when Pacific Electric painted the cars red. The script on the front changed but the cars were named the same, Echo and Rubio. Because the cars could not be seen as easily painted red, Pacific Electric decided to go back to white and let people see the cars once again from great distance as they ascended the six minute ride. In 1922, the cars got their final big change as the old opera cars were completely redone, but Lowe’s original carriage design stays intact. The cars have a more squared look and the top level is enclosed entirely in wood with glass windows.

Lastly, the photos can also be generally dated by the dress of the patrons riding in the cars. As the passengers move from the days of mining and railroad building to the advent of the automobile to the Roaring Twenties, it is reflected in their dress and accessories. And it is clear that the resort was designed for wealthier visitors, as most of the travelers were well-dressed.